Lt. Ahmed Ekrem's account of the battle with Russian Cossacks

that resulted in his captivity in July 1916.//

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I felt quite safe and secure that night because the entire day the fighting had taken

place on the main line a kilometer ahead and I had the 4th Regiment’s 13th Company

with me. Consequently, together with Rıza Efendi, we prepared our ammunition for

firing and lay down between the rocks. I thought to myself “I’ll have a good night’s

sleep in this safe spot and we’ll dig the trenches early in the morning.”

About 2 o’clock in the morning, my ears rang from the sharp sound of shells

exploding among the rocks. I woke up and thought first about the detachments

ahead of us. And even though I thought it was impossible that the enemy could

be approaching 100 meters in front of us, their shouts of “Hurrah!” proved me

wrong. At this time, the infantrymen beside us were firing. I realized that the

enemy was making its raid and had routed our detachments from their positions.

Consequently, I reckoned that our troops were in front and the enemy in back

so they probably headed for the top of the hill. Since in the darkness I couldn’t

see anything, in order to avoid hitting our detachments, which I thought had not

retreated, right away I had Sergeant Ömer point the fourth gun toward the pasture

with its barrel raised and told him to open fire across a wide area. My aim was

merely to create an effect, but just at that moment a bomb hit the infantrymen’s

trench next to us and exploded. I realized we could no longer stay here because

the bomb had come from behind us. The enemy had approached us from the rear,

from the Zimon side. So I yelled “leave the guns to God. We’re going up the hill!”

The gunners came to me with just the gun barrels, without the tripods. I

admonished them to go back and get the tripods and I waited for them to fetch

them. Right away, the enemy came to the gun positions. There was about 30 feet

between us. Those who had gone to get the tripods said the enemy had come so

we had no choice but to start to climb the hill. The enemy’s bullets whizzed by

our ears and their boistrous shouts of “Hurrah!” were chasing us, as well. We kept

on trying to climb the hill because otherwise we were sure to fall into the hands of

the enemy, whose exhaustion was overwhelmed by the scent of victory. As I said

before, the difficulty of moving on the steep and rocky ground was amplified by the

slippery grass, so I would fall back one step for every two I took. My desire to find

the summit spurred me on. But my mouth was open and my chest heaved up and

down, as my strength diminished with every step I took. I realized I could not go

any further because I did not have enough strength to take a breath. So I screamed

at the soldier with me “I can’t go on, you go on ahead!” A soldier came and took me

by the arm, allowing me to press on another 10 or 15 feet. He couldn’t carry me by

himself so another soldier came and took my other arm. I realized I was causing

them harm so I ordered them to “make sure the guns aren’t lost!”

Somehow, with my effort and the help of the soldiers we reached the summit, at

which time I collapsed. I told reserve officer Rıza Efendi to “inform the detachment

commander that we have come” but I realized that I should be the one to tell him

so I went to the detachment commander, who was next to a small fire burning ten

feet away, and told him that we had come, that we couldn’t bring the tripods with us

and that the enemy was fifteen steps behind us. In response, he said “the enemy

may not be able to come further than the rocks below.” No sooner did he say this,

though, then an infantryman came running, crying out “Sir, the enemy has penetrated

us!” Just behind him were four or five Russian soldiers screaming “all Ottomans

surrender!” and they came running up in front of the rocks where we were.

Russian Cossacks in the trenches at Sarıkamış, December 1914.

Together with the detachment commander, we screamed at and threatened our

soldiers to fire but at the same time we were fleeing to the rear. But when we

reached the rocks a bit to our rear there were more Russian soldiers shouting

“surrender! surrender!” and they mingled among us. We screamed at our

soldiers to fire and they did so, but in the darkness who could tell who was firing

at whom, since no one could tell who was friend and who was foe. When the firing

began a Russian soldier tossed a bomb at us, so we ran behind a big rock, where

Russian soldiers were waiting and they pressed their bayonets to our chests and

heads, shouting “Surrender!”

It was all finished at the point of a Russian bayonet, which was touching my head

next to my right ear. I stood motionless, lest that pointed iron scatter my brains.

Right away, some more Russian soldiers came, surrounded us and began to search

us. I didn’t have my revolver with me.

We were now taken at the point of six or seven Russian bayonets toward the

Russian lines. This was the worst, the darkest, moment of my life. The exertion

of climbing the hill and my consequent exhaustion made by legs tremble so I

couldn’t walk. My chest was pounding rapidly and I could hardly breathe. Up to

this point I had kept a professional reserve toward the regimental commander, who

was also the detachment commander, but now I had to lean on his arm in order to

be able to walk. The Russian soldiers who surrounded us took us to the battalion

headquarters – the rocks where the machine guns had been – and made us sit down

there. Our soldiers lit a fire and we sat around it, along with quite a few Russian

soldiers.

Dawn came. The Russian soldiers searching the area found our machine gun

tripods amid the rocks and brought them on wheeled platforms. The ammunition

was in saddlebags lying where we left them, since we couldn’t taken them with us

on padless horses in this steep terrain. A bit later they brought the gun barrels,

so at this point I realized that the gun barrels had been abandoned when they

couldn’t be carried and, consequently, had fallen into the enemy’s hands. Corporal

Ömer, the head of the 4th machine gun team, was wounded in his stomach from

a dumdum bullet and his intestines were hanging out. He died as he was being

taken to a bandaging place. Because it was he who was carrying the 4th machine

gun barrel, when he was wounded the barrel was dropped. The other gun barrels

were abandoned on the way by the soldiers who were carrying them. When I

thought about it I realized that I, who was carrying nothing, couldn’t make it to

the top of the hill because of the rocks and slippery grass, so I should have

understood how this corporal, with the barrel on his shoulder, couldn’t make it either.

In this way, the machine guns had fallen into the hands of the enemy. Fortunately,

while we were still among the rocks, the firing by the infantrymen next to us had

enabled the removal of our ammunition pack animals and a portion of our materials

at the top of the hill. When we got to the top and the enemy mixed in with us, the

soldiers I was with all fled and luckily for them they got away. Out of 16 soldiers,

three were taken prisoner.

Zimon-Çevrepinar today.

I’m now amazed that the others weren’t taken prisoner. It is remarkable that the

whole day there was fighting at the line a kilometer ahead of us, yet the reserve

detachments here were suddenly surprised by the enemy. The fact that we came

face to face with screams of “Hurrah!” from so close a distance means that the

forward detachments had failed miserably to do their job. The detachment

commander had ordered that “no one shall abandon his position without an order

to do so.” Yet, unfortunately, our forward detachments did not comply with this

order. In fact, they didn’t fire at the enemy but, even worse, they didn’t fire shots

to warn us of the enemy’s raid. They absconded in directions we still don’t know

of and completely abandoned the front to the enemy.

Yes, the detachment commander, when he gave the order, revealed his own position.

So besides ignoring the order not to abandon positions without orders, the forward

detachment commanders, knowing what an important and strategic position Taşlıca

Tepe was, that the reserve detachments were there with the detachment commander

and that they must not retreat by splitting their own line, did so anyway and without

firing warning shots to alert us of their retreat. Who knows under what compulsion

and for what reasons they retreated. Not one of these detachments’ officers or soldiers

was taken prisoner. Therefore, they didn’t retreat because of the enemy raid. Quite

the opposite, they deliberately abandoned their positions and it can be said that, in this

way, they left the rear detachments exposed to a sudden and disastrous calamity. Had

the companies and machine gun teams of the reserve detachments been aware of the

raid on the front line and had the detachment commander, in particular, been made

aware of this, the requisite defense could have been mounted based on the situation.

As a matter of fact, a defense was attempted against the enemy at close quarters but

the entire area was surrounded. So without being able to perform our duty, some of us

were able to get away and some of us were taken prisoner.

and that they must not retreat by splitting their own line, did so anyway and without

firing warning shots to alert us of their retreat. Who knows under what compulsion

and for what reasons they retreated. Not one of these detachments’ officers or soldiers

was taken prisoner. Therefore, they didn’t retreat because of the enemy raid. Quite

the opposite, they deliberately abandoned their positions and it can be said that, in this

way, they left the rear detachments exposed to a sudden and disastrous calamity. Had

the companies and machine gun teams of the reserve detachments been aware of the

raid on the front line and had the detachment commander, in particular, been made

aware of this, the requisite defense could have been mounted based on the situation.

As a matter of fact, a defense was attempted against the enemy at close quarters but

the entire area was surrounded. So without being able to perform our duty, some of us

were able to get away and some of us were taken prisoner.

The enemy attacked Taşlıca Tepe with two regiments – the 15th and 17th Cossacks.

The enemy units surrounded the hill from the north and from the east (from the pasture

and from Zimon) and, with a well-organized movement, stormed the hill

simultaneously. We knew this because the soldiers who pointed their bayonets at us

were from various battalions and because officers taken prisoner were brought to

different battalion headquarters. We did not give importance to the eastern portion,

the Zimon side, and did not put sufficient forces there. The terrain here is incredibly

steep. Yet the enemy advanced with ease and reached the summit at the same time as

the enemy forces coming from the north, effectively surrounding our soldiers on the

north, east and west and then infiltrating among us. There were 100 members of the

4th Regiment’s 13th Company in different spots here but because of the suddenness

of the raid they were unable to establish a solid line near the summit. As I noted

above, when we suddenly found the enemy among us our soldiers scattered.

The enemy units surrounded the hill from the north and from the east (from the pasture

and from Zimon) and, with a well-organized movement, stormed the hill

simultaneously. We knew this because the soldiers who pointed their bayonets at us

were from various battalions and because officers taken prisoner were brought to

different battalion headquarters. We did not give importance to the eastern portion,

the Zimon side, and did not put sufficient forces there. The terrain here is incredibly

steep. Yet the enemy advanced with ease and reached the summit at the same time as

the enemy forces coming from the north, effectively surrounding our soldiers on the

north, east and west and then infiltrating among us. There were 100 members of the

4th Regiment’s 13th Company in different spots here but because of the suddenness

of the raid they were unable to establish a solid line near the summit. As I noted

above, when we suddenly found the enemy among us our soldiers scattered.

For these reasons, the enemy was able to take this important hill at minimum cost.

We must be grateful, though, that the detachment commander ordered the cannon that

were here during the day moved to the division headquarters at night, saving them

from the enemy in the end. Otherwise, it would have been necessary to add four

cannon and the animals to the total of our losses. Our company’s first team was

located on the hill south of Zimon. When the enemy stormed the hill the next day the

soldiers there, together with two officers and the battalion doctor, were taken prisoner.

It was understood from the statement of the captured officers that when they saw their

situation was dangerous our team here withdrew early in the morning.

We must be grateful, though, that the detachment commander ordered the cannon that

were here during the day moved to the division headquarters at night, saving them

from the enemy in the end. Otherwise, it would have been necessary to add four

cannon and the animals to the total of our losses. Our company’s first team was

located on the hill south of Zimon. When the enemy stormed the hill the next day the

soldiers there, together with two officers and the battalion doctor, were taken prisoner.

It was understood from the statement of the captured officers that when they saw their

situation was dangerous our team here withdrew early in the morning.

It is my sincere conviction that our detachments on the front line displayed great

cowardice and treachery when they abandoned the line and that they are completely

responsible for causing this calamity.

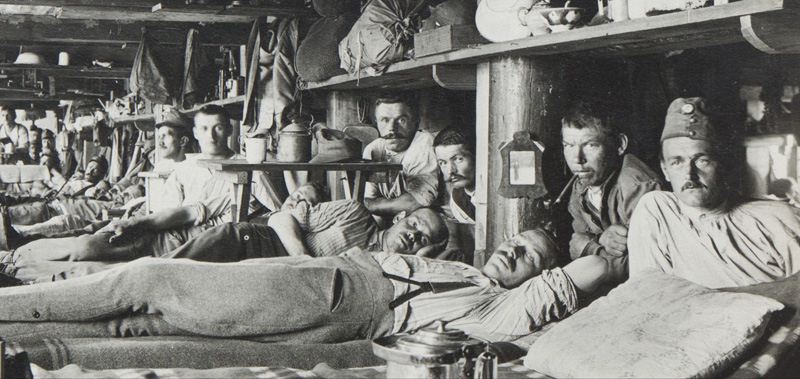

Ottoman POWs in a Russian prison camp, World War I.

cowardice and treachery when they abandoned the line and that they are completely

responsible for causing this calamity.

Ottoman POWs in a Russian prison camp, World War I.

Officers taken prisoner on Taşlıca Tepe

Detachment Commander and 52nd Regiment Commander Major Yusuf Ziya Bey

4th Regiment 4th Battalion Commander Captain Seyfuddin Ziya Efendi

52nd Regiment Machine Gun Commander First Lieutenant Ahmed Ekrem Efendi

4th Regiment 13th Company Commander First Lieutenant Ali Rıza Efendi

4th Regiment 13th Company Deputy Officer Fuad Efendi

52nd Regiment Machine Gun Officer Cadet Ali Rıza Efendi

Officers taken prisoner at the hill south of Zimon

52nd Regiment 3rd Battalion Doctor Captain Irfan Efendi

52nd Regiment Company Second Lieutenant İdris Azmi Efendi

52nd Regiment Company Second Lieutenant Fehmi Efendi

A Prisoner’s Song

Russia: Satılmış Gedik (near Kars)

August 332 (1916)

We fought on the Caucasus Front mightily mightily

One night we fell to the enemy and cried and cried

I cannot leave my beloved homeland, I cannot

I would not have left, the enemy broke away my army from my homeland

We walked for days and days, leaving our homeland

And wore the yoke of captivity

Subjected to all sorts of horrors, we were crushed, crushed

We found out what degradation, misery and imprisonment are

My beloved homeland...

I would not have left you...

Salutations to our mothers and fathers

Pray that we are delivered from this captivity

My beloved homeland, the place I love, I did not leave, I did not leave

I would not have left. The Muscovites separated me from my army, from my nation

Ahmed Ekrem

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

//END of Part II-Final//

//Ed. Note: Conclusion

After his time at the Satılmış Gedik prison camp, Lt. Ekrem went by

prisoner train into Russia during the months of December 1916-January

1917 and personal documents show that he was at the Russian prison camp

at Nerekhta, east of Moscow, in August and September, 1917. A year later,

though, in August 1918, Lt. Ekrem was in his hometown of Biga, in western

Turkey, evidently having benefitted from the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty signed

between Turkey and Soviet Russia on 3 March 1918.//

//END of Part II-Final//

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder