"Real Stories From Our History" by John Faris,

published in 1916. Here's the story of the journey of

first steamboat on the Ohio River - interrupted by the

famous New Madrid earthquake of 1811. (!)//

Until 1811 transportation on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers was by

means of keelboats, barges and flatboats. The keelboat is described

as being "long and slender, sharp fore and aft, with a narrow gangway

just within the gunwale, for the boatmen as they poled up the stream"

when they were unable to use their oars. Sometimes a low house

covered the keelboat, and it was then called a barge. The flatboat was

"an unwieldy box, and was broken up for the lumber it contained on

its arrival at its destination." Of course it was useful only in going

downstream. Many of the early immigrants loaded their goods on

flatboats, traveled by water as far as possible, then sold their means

of transportation, and completed their journey by land.

The success of Fulton's Hudson River steamboat led many people

to wonder if boats could not be constructed for use west of Pittsburgh.

The fact that ever-increasing multitudes were seeking new homes in

the West made steamboats on the Ohio and Mississippi seem very

desirable. But those who knew the rivers best felt that owing to the

treacherous currents and the shifting channels, steamboat traffic would

be impossible.

Finally it was decided by Nicholas J. Roosevelt, Chancellor Livingston

and Robert Fulton ot make a careful study of these currents and if the

results were favorable to build a boat run by steam. In 1809 Roosevelt,

who agreed to make the necessary investigations, floated on a flatboat

to New Orleans, carrying on his investigation as he went. Mrs.

Roosevelt, who accompanied her husband, said of the trip:

The journey in the flatboat commenced in Pittsburg, where Mr.

Roosevelt had it built; a huge box containing a comfortable bedroom,

dining room, pantry, and a room in front of the crew, with a fireplace

where the cooking was done. The top of the boat was flat, with seats

and an awning. We had on board a pilot, three hands, and a man cook.

We always stopped at night, lashing the boat to the shore. The row

boat was a large one, in which Mr. Roosevelt went out constantly

with two or three of the men to ascertain the rapidity of the ripple or

current.

Mr. Roosevelt stopped at Cincinnati, Louisville and Natchez, then the

only places of any importance between Pittsburgh and New Orleans.

To the leading men of these towns he stated his belief that steamboats

on the Ohio and Mississippi could be run successfully. River men as

well as businessmen laughed at him, declaring that he was an idle

dreamer.

But he went ahead with his arrangements, for he had made up his

mind to build a steamboat on his return to Pittsburgh. So confident

was he of the ultimate success oof the project that he purchased and

opened coal mines on the banks of the Ohio and arranged that heaps

of coal should be stored on the shore, in readiness for the vessel he

was sure would need the fuel for its engines.

From New Orleans he went to New York by sea. There, capitalists

were interested in his report. In 1811 he found himself in Pittsburgh,

ready to work on the steamboat. Men were sent to the forests to cut

timber for ribs, knees and beams. These were rafted down the

Monongahela to the shipyard. Planking was cut from white-pine logs

in the old-fashioned saw pits. A shipbuilder and the mechanics

required were brought from New York.

Curious visitors watched the growth of the frame and prophesied

failure. But Mr. Roosevelt smiled at their doubts. At last the boat,

one hundred and sixteen feet long, was ready and was christened

the New Orleans. There was a ladies cabin containing four berths

and Mrs. Roosevelt announced her intention to occupy one of them.

Friends in Pittsburgh appealed to her to give up the dangerous

project but she insisted that there was no danger - she believed in

her husband.

Mrs. Roosevelt's brother J.H.B. Latrobe wrote that "Mr. Roosevelt

and herself were the only passengers. There was a captain, an engineer,

the pilot, six hands, two female servants, a man waiter, a cook and an

immense Newfoundland dog. Thus equipped, the New Orleans

began the voyage which changed the relation of the West - which

may almost be said to have changed its destiny."

Eager watchers at Pittsburgh saw the vessel swing into the stream

and disappear round the first headlands; their prophesies of disaster

at the very start had not been fulfilled. The pilot, the captain and

the crew had their misgivings but these were soon set at rest by

the behavior of the boat.

At Cincinnati, which was reached on the second day after leaving

Pittsburgh, an enthusiastic crowd welcomed the vessel. But still

there were doubters. "Well, you are as good as your word. You

have visited us in a steamboat but we see you for the last time.

Your boat may go down the river but as to coming up it the very

idea is an absurd one."

The doubters in Cincinnati were convinced when the boat returned

from Louisville, having been stopped by the lack of sufficient water

to carry it over the Falls. When the stage of water was right, though,

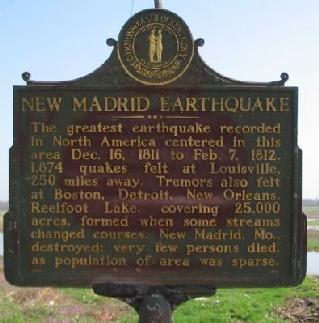

Louisville was safely passed. Then began days of anxiety, not due

to the steamer's failure to mind her helm but to the great earthquake

of 1811 (New Madrid), which struck terror into the hearts of thousands,

changed river channels and worked other transformations in the

physical appearance of the country for hundreds of miles.

At New Madrid, Missouri, scores of people begged to be taken on

board the steamboat. They reported that the earth had opened and

that many houses and their inhabitants had been swallowed up.

Other settlers hid from the boat, thinking that its appearance was

a part of the calamity that had overtaken the town.

Indians, too, were frightened at the approach of the steamer.

They felt that the smoke from her stacks had something to do with

the heavy atmosphere which accompanied the earthquake and that

she was to be accounted for in much the same way as the great

comet that had appeared in the heavens. Once, when the sound of

escaping steam was heard, it was thought that the comet had fallen

into the river.

One night the New Orleans anchored just below an island. In the

morning the vessel was in the middle of the river. At first it was

thought that she was adrift but it was found that the hawser with

which the vessel had been moored still held. Then it was evident

what had happened: during the night the island had disappeared,

having been broken up by an earthquake.

At last, the New Orleans passed out of the field of the earthquake

and Natchez and New Orleans were reached in good time, ending

the first voyage of a steamboat on the Ohio and Missippi rivers.

Nicholas J. Roosevelt (1767-1854)

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder